*Or: How I learned to stop worrying and love the lockdown

(Note: this is from a letter of husband John to brother-in-law Larry, which I thought too good to hoard.)

Neither of us do jigsaw puzzles, except those we attempt to assemble while entertaining our six year old granddaughter, Danica. Those would be your 30 piece puzzlers. The one offered to us in various shades of dark brown,  medium brown, light brown and the same assortment of blues, all rocks and water and sky, contains one thousand five hundred pieces.

medium brown, light brown and the same assortment of blues, all rocks and water and sky, contains one thousand five hundred pieces.

Seven weeks ago we gamely dumped it out onto the dining room table, for which we have no other need at present what with it being summertime and the eating is in our summer dining room, i.e., the front porch. And, of course, no one can come to join us. Would you believe that I put the last piece in place Sunday afternoon?

It was not an easy puzzle. In order to complete it, I had to dig up the 1.5 kilogram rubber mallet that I purchased several years ago to help me with a ceramic tile project. Even with a rubber mallet, you have to be rather circumspect when working with ceramic tile. But that is not the case with jigsaw puzzle pieces. It took only three blows delivered with all the power I could muster from my admittedly somewhat enfeebled frame, to drive in that sucker. All that is left to do is touch it up with the appropriately coloured felt pens.

You must disabuse yourself of any musings you are entertaining about the sort of idiots who pass their time in this way for I have discovered that jigsaw puzzles are an ideal method for maintaining physical fitness. By three o’clock in the afternoon I am usually overtaken by lethargy. I have had breakfast and coffee and a nap and a stick of celery for lunch and am ready for some demanding physical activity to re-energize me. Voila! There it is. The Puzzle.

My pajama sleeve brushes a puzzle piece onto the floor: a knee bend is required.

Cecelia’s hand hovers over a piece I have been seeking for days: a horizontal lunge will take care of it.

My elbow knocks three pieces onto the floor: a forward crawl under the table is in order.

The piece in my hand looks to fit perfectly on the other side of the puzzle which is about three feet away (one thousand five hundred pieces makes a bloody big puzzle): a lateral stretch does the trick.

Subtle colour shades can be discerned only by squatting down until the puzzle surface is viewed from its edge. Warning. People over eighty should not attempt this while holding a martini.

I could go on and on.

And have.

(Signed off)

*I have not been keeping up my end of the blog scene this last while due to becoming thoroughly immersed in my new novel, which I call my Pandemic novel even though it has nothing to do with pandemics. I trust you all enjoy hearing from John.)

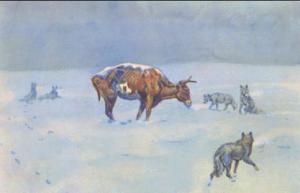

knees about to cave in, the animal is without resources. In a moment, the wolves will be upon it, ripping it apart, feasting on the entrails. Blood on the snow. Or maybe they won’t wait for it to collapse. Maybe they’ll bring it down… same result. Obviously, the chinook didn’t arrive in time for that steer.

knees about to cave in, the animal is without resources. In a moment, the wolves will be upon it, ripping it apart, feasting on the entrails. Blood on the snow. Or maybe they won’t wait for it to collapse. Maybe they’ll bring it down… same result. Obviously, the chinook didn’t arrive in time for that steer. Ten years later, she went to England and became a Lesbian, leaving him with three children. So then he married Judy, a home economist many years his junior who, he thought, would be good with the children, but she wanted to have her own cooking show on TV and went to Toronto. So he employed a nanny, very attractive, and when the inevitable happened, Judy returned and read the riot act, and after that divorce he married Inga, an aerial gymnast, who, it turned out, had a bad heart, which they found out about when she went plonk down into her bowl of breakfast cereal Christmas morning, an unusual death at such a young age but, apparently, it was because of the drugs. At least Ron was a successful lawyer so he could manage his own legal proceedings and didn’t have to go bankrupt like so many of his clients.”

Ten years later, she went to England and became a Lesbian, leaving him with three children. So then he married Judy, a home economist many years his junior who, he thought, would be good with the children, but she wanted to have her own cooking show on TV and went to Toronto. So he employed a nanny, very attractive, and when the inevitable happened, Judy returned and read the riot act, and after that divorce he married Inga, an aerial gymnast, who, it turned out, had a bad heart, which they found out about when she went plonk down into her bowl of breakfast cereal Christmas morning, an unusual death at such a young age but, apparently, it was because of the drugs. At least Ron was a successful lawyer so he could manage his own legal proceedings and didn’t have to go bankrupt like so many of his clients.” below according to the thermometer outside the kitchen window and only a wooden shell between us and a northern Alberta January. Outside, the wind might howl, the snow might drift up to the windowsills, but I was warm and safe in what the Danish call my hygge place. I wonder now if my parents were frantic with worry, three small children, one a babe in arms. If so, I felt none of it, wrapped in a blanket, flooded by a sense of well-being because hair washing day was over and would not happen again in what to me was a foreseeable future. Granny was there, too, with home made bread clipped into a wire toaster held over the stove until one side started burning and, so, for me the sense of familiar coziness will forever include the smell of burning toast.

below according to the thermometer outside the kitchen window and only a wooden shell between us and a northern Alberta January. Outside, the wind might howl, the snow might drift up to the windowsills, but I was warm and safe in what the Danish call my hygge place. I wonder now if my parents were frantic with worry, three small children, one a babe in arms. If so, I felt none of it, wrapped in a blanket, flooded by a sense of well-being because hair washing day was over and would not happen again in what to me was a foreseeable future. Granny was there, too, with home made bread clipped into a wire toaster held over the stove until one side started burning and, so, for me the sense of familiar coziness will forever include the smell of burning toast. I once had a job in the Edmonton Public Library where a rickety old elevator took me down to the archives in the cellar, a sort of sub-basement. That was the year I spent the entire winter in the dark.

I once had a job in the Edmonton Public Library where a rickety old elevator took me down to the archives in the cellar, a sort of sub-basement. That was the year I spent the entire winter in the dark. thing for years. Eaten, slept, cavorted, contrived with it. You have put everything of yourself into it – your energy, emotions, intellect. You have a closer relationship with these characters of your imagination than you do with your real-life friends and family. And then it’s over. You are caught in a great yawning silence. What to do?

thing for years. Eaten, slept, cavorted, contrived with it. You have put everything of yourself into it – your energy, emotions, intellect. You have a closer relationship with these characters of your imagination than you do with your real-life friends and family. And then it’s over. You are caught in a great yawning silence. What to do? dishwashing machines, we always had dishes in the sink. By the time we finished arguing about whose turn it was to do what, we had run out of time.

dishwashing machines, we always had dishes in the sink. By the time we finished arguing about whose turn it was to do what, we had run out of time. as put it off for another time. Avoidance is the word. Still, it kept putting itself in my way, foyer table to kitchen counter to sideboard and back. Until, finally, “Oh, all right,” I found myself saying, just the other day. I sat down to read.

as put it off for another time. Avoidance is the word. Still, it kept putting itself in my way, foyer table to kitchen counter to sideboard and back. Until, finally, “Oh, all right,” I found myself saying, just the other day. I sat down to read.